The Rise and Fall of the Kersten Knitting Empire.

By Jack R. Melkonian, Dipl. Ing. (FH)

The accession of Peter I, also known as Peter the Great, in 1689 ushered in and established the social, institutional, and intellectual trends that were to dominate Russia for the next two centuries away from the Byzantine heritage. On May 16th 1703 Peter himself laid the foundation stones of Saint Petersburg, the future capital of Russia. In 1712 the transfer was made, and members of the nobility and merchant class were compelled to move to the new capital and build houses for themselves.

The need to modernize the country made Peter a great traveler visiting England, Holland and France, sometimes officially, sometimes incognito where he studied ship building, carpentry, mining, and the production of glass and textiles.

The 12th May 1717, Peter accompanied by the Duke d’Antin visited the “Manufacture des Gobelins”, at Avenue des Gobelins no. 42 in Paris. He was so fascinated by the work carried out in that workshop that he spent five hours talking to the workers and returned again to the location before leaving Paris. His impression must have been discussed after the return to his residence on the Neva since in 1720 Peter inaugurated his own tapestry workshop in Saint Petersburg by engaging Jean-Baptisted Bourdin,

A Frenchman named Mavrion opened a knitting mill producing silk stockings in Moscow around 1718.

During the same year a merchant named Miller founded a similar mill.

It is however only in 1855 that another French merchant named Ivan Osipovich Natus, installed the first knitting enterprise in Saint Petersburg at Bolshaya Spasskaya Street no. 26.

By the middle of the 19th century there were 9 small knitting mills in Russia. Together these enterprises employed 181 people. So far one can say that the pioneers were the French, and it can be assumed that the visit to Paris by Peter, more than 100 years ago, must have attracted many of them to try their luck in this underdeveloped empire.

Another piece of conversation, 50 years later was the portrait of Catherine II also known as Catherine the Great, woven in silk by Philippe de La Salle. At that time the property of Voltaire and close friend of the empress. This masterpiece in woven silk must have left another great impression on the Russians since in June 1771 Catherine mentions her portrait in a letter to Voltaire. In 1789 Nikolai Mikhailovich Karamzin visits the Chateau de Ferney, the former residence of Voltaire, and contemplates in front of the same picture. Gogol writes on the 27th September 1836 “I saw the portraits of all the friends of Voltaire, those of Diderot, Frederic and that of Catherine.

But in 1866 it was a German, Friedrich–Wilhelm Kersten, who started one of the largest textile empire in Russia. At that time there was already an important German community in Russia, some of them descendents from elites-urban bourgeoisie from the Baltic countries, others from the German entourage of Catherine, her cousin-husband Peter III, formerly the Duke of Holstein-Gorp, and of course the many who under contracts were hired for their skills and knowledge, not to speak about the adventurers who came to make a quick ruble.

Judging from the sketchy records it must be assumed however that Kersten emigrated during his life time from his native Germany to Russia and was initially trading in textiles. In 1866 he bought the workshop of Natus, took Russian citizenship, adopted Orthodoxy and since that time has been known as Vasily Petrovich Kersten. Soon he opened another knitting workshop at Ligovsnaya Street no. 32 to mend knitted stockings. He mainly used the labour of home workers. In 1870 an All-Russian exhibition of manufactured goods was held in Saint Petersburg. The factory showed wool and cotton stockings, gloves, vests and dresses. Already at that time his selection of goods was larger than that of his competitors. He was awarded his first medal and became an honorary citizen. In 1870 the V.P. Kersten employed 165 workers inside the factory, and 105 external.

A year after the exhibition V.P. Kersten organized the first mechanized laundry in Russia at Bolshaya Spassnaya Street no. 22-24 close by the knitting factory he had bought from Natus.

In 1883 another German, Karl Marx, a social economist, died in London and leaving behind “Das Kapital”. But the same man, co-author of the “The Communist Manifesto”, wrote in a letter to his friend Friedrich Engels: “Grey, dear friend, are all the theories, only business is green”.

In 1883 Kersten’s hosiery and knitwear factory as well as the laundry which served military and educational institutions had been integrated into a well organized highly profitable business. Things looked “green” for Vasily Petrovitch, and who cared about Marx’s Manifesto?

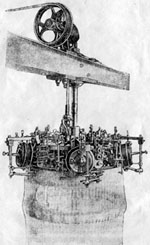

Germany became Kersten’s main source of new equipment and old hand-knitting machines were modernized. The oldest machines which survived the Revolution and the Soviet Period were manufactured between 1899 and 1905 by C.Terrot & Soehne of Cannstadt. These unique sinker wheel machines whose cylinder and central axle were suspended from an overhead beam were the only single-jersey machines capable of automatically transferring needle loops to the left or to the right. They were used to produce underwear fabrics for the army during the first and second world war. The last three of these historical machines were saved from the scrap yard by the author and returned to Germany.

The Kersten enterprise was the biggest industrialized knitting factory not only in Saint Petersburg but in the whole of the Russian Empire. His mechanized laundry had been the only one for many years.

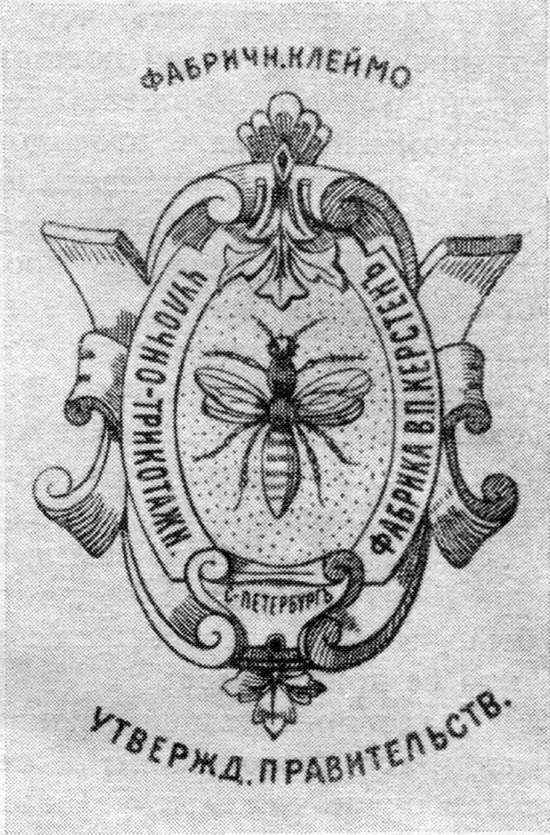

Kersten knew from the beginning how to make use of both a domestic and factory production system. It is not surprising that he chose a BEE as a trade mark, being the symbol of diligence.

After his death in 1884 his business was inherited by his wife Ekaterina Petrovna Kersten. It was a difficult task for her to run the business. After a few years she decided to appoint the 22 years old Andrey Semyonovich Edelman who worked at her factory and knew the knitting production well. She eventually adopted him as her son, and he got the name of Kersten. In 1899 he became production manager both of the knitwear factory and the laundry, as well as the affiliated enterprises. Since that time A.S. Edelman, now Kersten, in fact has become the head of the factory supported by his brothers Nikolay and Peter Edelman who later on changed their name too to Svetlanov.

In 1904, immediately after Ekaterina Kersten’s death her adopted son Andrey organized a group of companies called “THE V.P. KERSTEN TRADE HOUSE”. Among the founding partners were his wife and his brother Nikolay. The authorized capital amounted to half a million rubles.

Andrey Semyenovich knew how to use any opportunity to develop business, and increase profit. In 1905 the Kersten Trade House employed over 640 workers of which 440 worked in production and 207 in the laundry. In 1909 the Kersten Trade House turned into The V.P. Kersten Joint-Stock Company with Andrey at the top. He continued increasing the production. During 1909 his factory used about 30000 poods (one pood = 16.3 kg) of cotton and wool yarn. The suppliers were both Saint Petersburg and Polish spinning mills. In 1910 he began building his own spinning facility and within one year the new plant was operating. The cotton raw material came from the Russian province of Turkistan (now Uzbekistan), formally annexed in 1876. No doubt the natural silk used in ladies stockings came from there too.

It was only in the late 1960’s that this section of the Kersten factory was transformed into a department to accommodate full fashioned Cotton machines made by Monk-Cotton of Leicester. Some of these machines, saved by an Englishman, returned a shortly after Perestroika to their country of origin.

The same year a making-up workshop to produce bed-sheets started working. That year the turnover of the Joint-Stock Company amounted to 1’578’000 rubles, i.e. twice as much as 5 years ago. Net profit rose to over 138’000 rubles.

In 1913 a new building for the main office was erected. By 1916 the whole complex of structures which is now to be called an old factory, had been constructed. The beautiful main entrance in brick and sandstone, richly decorated in an Art Nouveau style, is still preserved. The impressive stair case with its stained glass windows remind the visitor of past glory. To-day almost a hundred years later the building as commissioned by Kersten has not changed and the near-by barracks filled with young Russian solders remind you of the days when their underwear were knitted on these Terrot machines which lasted for ever.

On the eve of World War One the factory had 689 knitting machines, of which 87 were hand operated stocking machines, 129 sewing machines, 65 spinning machines, and 2250 people employed. The factory worked in 2 shifts to make maximum use of the expensive imported equipment. The factory together with the laundry had a book value of 3’150’000 rubles. The total turnover in 1913 amounted to about 2’500 000 rubles and the profit rose to 359’340 rubles. It is interesting to note that since 1913 the company became the appointed supplier to the Duma, the lower house of Parliamant. Kersten had clients in 81 Russian towns. The range of knitted articles produced by the company was continuously widening. The factory often got medals at All-Russian Exhibitions.

On the Great Gold Medal which the factory got in 1910 it was written “ For the Diligence and Art”.

The business continued growing making the Kersten factory the biggest stocking and knitwear factory in Russia. It had no competitors on the home market and was considered the uncrowned king of knitwear. In 1912 there were 94 knitting factories in the whole empire including some parts of Poland and the Baltic region with the total number of 9484 workers. There were 13 factories in Russia employing 2582 workers. The year the whole knitting industry of the Russian Empire produced knitted products at the amount of 15’830’000 rubles. The Russian knitting enterprises manufactured knitted products at a value of 4’430’000 and the Kerstens for 1’770’000 rubles. Therefore that year the Kersten factory output amounted to 40% in value of the total production of knitted goods in Russia. The main product manufactured by the factory at that time was the underwear. In 1913 the factory produced 97% of the underwear, and 20% of stockings of the total output in Russia. Despite a 2-shift operation the company could not meet the increasing demand for knitted articles.

During the War from 25th August 1914 to 7th March 1916 the factory was supplying the army with underwear to the amount of 5.0 million rubles. Whereas in 1913 the plant used 44.8 thousand poods of cotton yarn, in 1916 the quantity increased to 104.3 thousand poods. The laundry too worked a lot for the army. The Duma continued to be Kersten’s other important State clients.

The outbreak of World War One in 1914 brought an upsurge of patriotic fervour. Saint Petersburg became Petrograd. Importation of equipment made in Germany became politically impossible. Kersten rather faithful to his German suppliers had to switch to British, American and Swedish manufacturers. Despite all these difficulties the factory output increased. In 1916 176 machines were bought abroad. That year the company operated over 1000 machines, among them 520 knitting, 282 stocking , 320 sewing and 61 spinning machines. By September of 1917 the number of workers had reached the record of 2700.

A business started 50 years ago with a couple of dozen workers turned into a big company with a total turnover of 12’869’000 rubles and its products widely known in Russia. The net profit amounted to 564’000 rubles. The number of shareholders also increased across the border to Finland. Adrey Kersten had become not only a manufacturer but a shrewd investor looking for new opportunities outside the textile industry. He placed money in the goldfields of the Vitum river in East Siberia. Such new activities limited his activity in the Petrograd factory, and finally in 1917 he resigned from the chairmanship, and handed over the management to his assistant A.A. Pini who in turn handed the job over to Peter Semyonovitch Svetlanov, the brother of Kersten. On May 27th 1917, an extraordinary meeting of shareholders was held where Kersten’s colleagues expressed their deep gratitude for his services. So the activity of the Russian King of Knitting came to an end. At the end of 1917 Andrej Semyonowitch Kersten, nee Edelman, packed his bags and left Russia for Finland, never again to return to the country where he built one of the most successful Russian textile company of the 19th century.

On the 7th November 1917 a new page was turned in the long history of the Russian empire. Petrograd eventually became Leningrad. The man who gave the name to this historical city may not have known about Mr. Marx’s ironic remark, who’s scholar he was, that all theories are grey, and grey the life of Russia became. The name of V.P. Kersten was kept until 1922 and that too was changed to the Red Banner Combine.

The factory continued operating under various appointed managers. Some of them outstanding and patriotic, always supported by a very dedicated work force. During World War Two the factory continued producing badly needed underwear for the army. A bomb hit the building and brought the factory to a stand-still. During the winter blockade the workers knitted by hand socks and other items for the soldiers. In April 1942 some knitting machines have been put into operation. In September two workshops were reopened and the stocking and sewing production resumed. The more effective restoration of the knitting factory became possible only when the blockade of Leningrad ended.

By 1954 the factory employed 10000 workers, 2/3rd of them worked in the stocking production and knitwear making-up.

By 1967 two subsidiaries had been constructed. About 1000 machines were installed there. In 1967 at the Red Banner factory, not including subsidiaries, there were 2050 seamless stocking machines, 160 full fashioned (Cotton) machines, 860 circular knitting machines, 90 high speed warp-knitting machines, 73 dyeing machines etc. By now the Soviet Union was almost self sufficient with its own knitting machines produced in Leningrad, Tula, Czernowtsy, Poltava and Orsha. The former GDR, Czechoslovakia and Romania too became suppliers to this factory.

But when Breshnew took over in the 60’s the decline of the Soviet economy began. It was a slow but continuos process which gradually led to the collapse of the whole system. Michael Sergeyevitch Gorbachew opened up the Soviet Union to the world and lots of new ideas but also uncontrolled imports of textiles poured into the country. Large factories like the Red Banner where not prepared to compete against an onslaught of cheap imports nor was the wise old Kersten around to stir the ship out of trubled waters.

As the great Communist experiment came to an end, so did what Friedrich–Wilhelm Kersten started a 120 years ago. The Russian people and so many others paid dearly for what Mr. Marx called “Grey Theories”. Ironically both were Germans and the bomb which hit the factory in 1942 too.

********Copyright of “Rise and Fall of the Kersten Knitting Empire” is the property of the author and the text may not be copied without the express written permission of the author.